"Tension in Poetry"

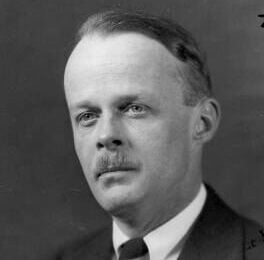

Allen Tate

Biography

American poet, critic, novelist, and teacher Allen Tate was born John Orley Allen Tate on November 19, 1899. The son of a Kentucky businessman and his Virginian wife, Tate was born and raised in Kentucky. His identity as a Southerner consumed his lifestyle, poetry, and social commentary throughout his entire career.

Tate inherited his love of English literature from his mother, and he studied at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee in 1918. At Vanderbilt, he became very close with an informal group of Southern intellectuals and poets, who called themselves “the Fugitives”. The Fugitives consisted of Robert Penn Warren, Donald Davidson, Merrill Moore, and Tate’s instructor, John Crowe Ransom. Tate was the first undergraduate student to be invited to join the group of poets as they read and commented upon their own poetry and that of others.

In 1922, the group began publishing The Fugitive, a poetry magazine that ran for three years. The magazine wanted to prove that southerners could provide valuable contributions to the genre of poetry. In Tate’s time and even today, there is a long-held belief that southerners are simple, ignorant, and dumb. In the American North, there was (and still is) a prejudice against southerners because of their dialect and the way they hold onto tradition. For much of American literary history, the Southern voice was largely ignored, which only escalated after the American Civil War. Tate and the Fugitives worked to combat that.

In 1928, Tate published his first collection of poems, Mr. Pope and Other Poems, and his first biography, Stonewall Jackson: The Good Soldier. That same year, he and his family left the United States for two years to travel and live in Europe. Tate met Ernest Hemingway and Gertrude Stein as well as his literary hero, T.S. Eliot, during his time abroad.

After he returned to the United States, Tate once again settled in the South in Tennessee. Tate taught at Southwestern College in Memphis from 1934 until 1936. He was named poet laureate of the United States from 1943 to 1944. Afterward, he joined The Sewanee Review, an American literary magazine, which became one of the foremost literary magazines in the United States under his editorship. He taught at the University of North Carolina, Princeton University, and finally at the University of Minnesota from 1951 until his retirement in 1968.

In 1970, Tate published The Swimmers and Other Selected Poems. In 1972, he was hospitalized for ten days with bronchitis and emphysema. His health never really improved, and he was hospitalized sporadically throughout the 1970s. His final collection, Collected Poems, 1916-1976, was published in 1977. Tate died on February 9, 1979, and was buried in Sewanee, Tennessee.

Tate graduated from Vanderbilt in 1922 and began working as a critic in 1924. The first magazine he worked for was the Nashville-based Tennessean, and he later worked for The Nation, Hound & Horn, Poetry magazine, and others. He moved to New York City in 1924 and began a friendship with fellow poet Hart Crane. Tate met novelist Caroline Gordon in 1924 and married her in May 1925. The two had their first daughter in September that year.

The essay has three parts.

Part 1 deals with the fallacy of communication in poetry.

Part II defines tension in poetry and explains its importance.

Part III gives the final example of the significance of tension.

Part I – Fallacy of Communication

Mass language, says Tate, is the medium of communication. Tate illustrates the point with some examples. The first example is “Justice Denied in Massachusetts,” a poem by Miss Millay$ [see notes].

The poem received much attention at its publication in 1927. But Tate says that the poem did not clarify how the judicial execution of two migrants—Sacco and Vanzetti—has something to do with the rotting of crops and the general aridness in Massachusetts. The poem is an example of the fallacy of communication in poetry because it is obscure. The poem makes sense only for those who share the feelings of the poet or her contemporaries.

Another example of obscurity is found in the poem “The Vine” by James Thomson. The language here appeals to an affective (emotional) state. It does not have a coherent literal or implied meaning. The more closely one examines the lyric, the more obscure it becomes. The imagery does not add anything to the general idea of the poem.

The wine of love is music

And the feast of love is song

When love sits down to banquet

Love sits long

Sits long and rises drunken

But not with the feast and the wine

He reeleth with his own heart

That great rich vine.

Another example is Cowley’s ‘Hymn: To Light.’

The violet, springs little Infant, stands,

Girt in thy purple Swaddling – bands:

On the fair Tulip thou dost dote;

Thou cloathst it in a gay and party-colored Coat.

Tate says that both poems are failures. ‘The Vine’ is a failure in denotation. ‘Hymn: To Light’ is a failure in connotation.

[Denotation= the act of denoting. The primary, literal, or explicit meaning of a phrase or symbol. The word is a contrast to connotation. “The building is on fire’—‘fire’ is used to denote external conflagration. “ My heart is on fire’—‘fire’ does not mean external fire. The word connotes excitement].

The Vine is a failure in denotation. “The language of the poem lacks objective content. Take music and song. The context does not allow us to apprehend the terms in extension. There is no reference to objects that we may distinguish as ‘music’ and ‘song’. According to Tate, we can even revert the idea and say that the wine of love is a song and the feast of love is music. Nothing will change. Thus the poem is meaningless.

‘Hymn: To Light ’is a failure in connotation. The connotations of violet, swaddling bands, and light (represented by the pronoun ‘thou’) give us a group of images. We can appreciate them only if we forget the denotative meanings of the terms. The poet uses violets, diapers, and light without referring to the denotative aspects at all. The group will become unified if we forget the denotative meanings of them.

Tate calls these poems absurd because good poetry is a unity of all the meanings from the furthest extremes of intension and extension. “The reader’s recognition of the action of this unified meaning is the gift of experience, culture, and humanism. The powers of discrimination here are not deductive powers but total human powers”. They apply to poetry, a single experience of the medium. Thus these kinds of poetry suffer from the fallacy of communication.

Part II defines the term and explains its importance.

Definition of Tension in Poetry

Tate has invented the term by chopping off the prefixes in and ex from intension and extension. Extension refers to extensive or logical, or denotative meaning in poetry. On the other hand, intension refers to the intensive or connotative meaning of poetry. A successful poem is one in which these two meanings are in a state of tension. Tate asserts that it is the life of the poem.

- Tate says that the meanings selected by the readers vary according to personal interests. The selection is always between the extremes of intension and extension.

- The Platonist will tend to stay very close to the extension end. He might decide that Marvell`s ‘To His Coy Mistress’ recommends immoral behavior’s to young men. It is, of course, one ‘true’ meaning of the poem.

- However, the full tension of the poem will not allow the readers to entertain it exclusively. The poem has an intensive meaning too. These meanings are sensuality (extensive) and asceticism or spirituality (intensive).

Then Tate gives another example. He quotes from Donne`s love lyric, A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning. Tate quotes the lines which contain the gold conceit. Here, the poet compares the souls of the lovers and their unity with the uniqueness of gold. The soul is non-spatial. The poet uses a spatial image (that of gold) to contradict it. However, the denotation of the gold contains the full meaning of the passage. Extension and intension are one here and enrich each other. Tate gives us many other examples from the Metaphysical, Symbolists, and Shakespeare to prove his point. He says that these lines can be used as ‘touchstones’ in the Arnoldian sense.

Part III gives the final example of the significance of tension.

In the third part of his essay, Tate takes a tercet from The Divine Comedy (by Dante 1265-1321).

The tercet from Inferno provides an excellent example of tension.

The context: Paolo and Francesca were illicit lovers. Dante meets them in the Second Circle of hell. They are whirling in a high wind. The wind is the symbol of lust. When Francesca speaks to the poet, the wind dies down. She tells him where she was born:

The town where I was born sits on the shore,

Whither the Po descends to be at peace,

Together with the streams that follow him.

Here the literal meaning is that she was born in a town on the Sea-shore. Here the river Po falls along with the tributaries. But the metaphor is more than just the description of the place. Dante pictures the streams of the river as chasing the Po down to the sea. Francesca has told Dante where she lives using lucid language but has told him more than that. She fuses herself with the river Po where she was born.

We see the pursued river as Francesca in hell. Tributaries pursue the river. Similarly, lovers follow Francesca. Lust (symbolized as wind) follows her.

The tributaries that pursue a river become one with the river as they flow into it. Similarly, Francesca has become one with her lovers, her lust. She has become absorbed by the sin of lust—she becomes the sin. In the Inferno, the damned are incarnations of their sins.

The wind of lust is an image. It is a visual as well as an auditory image. Francesca is heard by the poet when the hissing sound of the wind dies down. After the wind abates, we hear the susurration (continuous whispering sound) of the descending Po. Thus we see and hear the sin. Both intension and extension become one. Tate quotes these lines as a supreme example of tension in poetry.

Questions & Answers

1. What did Allen Tate write about?

Allen Tate wrote about Southern American history. He was deeply influenced by his connection to the South and wrote extensively on the need to get away from industrialization and back to a natural, agrarian lifestyle.

2. Where did Allen Tate really come from?

Allen Tate was born in Winchester, Kentucky. He spent most of his youth in Kentucky, Nashville, Tennessee, and the District of Columbia because his family moved around so much.

3. What, according to Allen Tate, constitutes tension in poetry?

Allen Tate believed that tension was needed for a work to be complete/whole. He believed a mutually beneficial relationship between extension (the literal meaning) and intension (the metaphorical meaning) created tension in literature.

4. Who was Allen Tate?

Allen Tate was a twentieth-century poet, literary critic, novelist, biographer. He wrote primarily Southern poetry.

5. Was Allen Tate a New Critic?

Yes, Allen Tate is considered a leading exponent of New Criticism. The New Critics emphasized close reading as the best way to understand a text. This formalist movement insisted on the intrinsic value of a work.