"My Boyhood Days"

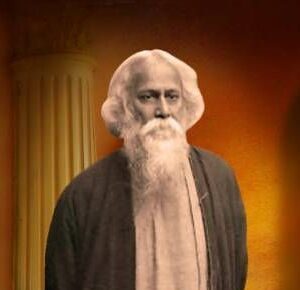

Rabindranath Tagore

Biography

My Boyhood Days (Chhelebela, 1940) is Tagore′s second memoir of his childhood days, written when he was nearing eighty. He describes, without a trace of self-pity, the spartan life he had to lead under his father′s instruction. The sense of wonder and delight in the seemingly commonplace experiences of boyhood helped him become a great poet.

Rabindranath Tagore was born May 7, 1861 in Calcutta, India into a wealthy Brahmin family. Tagore received his education at home. He was taught in Bengali, with English lessons in the afternoon. Tagore spent a brief time at St. Xavier′s Jesuit school, but found the conventional system of education uncongenial. In 1879, he enrolled at University College, at London, but was called back by his father to return to India in 1880. During the first 51 years of his life, he achieved some success in the Calcutta area of India where he was born and raised with his many stories, songs and plays. His short stories were published monthly in a friend′s magazine and he even played the lead role in a few of the public performances of his plays. Otherwise, he was little known outside of the Calcutta area, and not known at all outside of India. This all changed in 1912 when Tagore returned to England for the first time since his failed attempt at law school as a teenager. Now a man of 51, his was accompanied by his son. On the way over to England he began translating, for the first time, his latest selections of poems, Gitanjali, into English. Almost all of his work prior to that time had been written in his native tongue of Bengali. Tagore′s one friend in England, a famous artist he had met in India, Rothenstein, learned of the translation, and asked to see it. Reluctantly, Tagore let him have the notebook. The poems were incredible. He called his friend, W.B. Yeats, and talked Yeats into looking at the hand scrawled notebook. Yeats was enthralled. He later wrote the introduction to Gitanjali when it was published in September 1912 in a limited edition by the India Society in London. Thereafter, both the poetry and the man were an instant sensation, first in London literary circles, and soon thereafter in the entire world. Less than a year later, in 1913, Rabindranath received the Nobel Prize for literature. He was the first non-westerner to be so honored. Overnight he became famous and began world lecture tours promoting inter-cultural harmony and understanding.

Full Summary

Chapter 9: Anxious Days and Sleepless Nights

Chapter 10: A Harder Task Than Making Bricks Without Straw

Chapter 11: Making Their Beds Before They Could Lie on Them

Chapter 13: Two Thousand Miles for a Five-Minute Speech

Chapter 14: The Atlanta Exposition Address

Chapter 1: A Slave Among Slaves

Booker T. Washington recounts his childhood as a slave in Franklin County, Virginia. Because of his slave status, Washington is ignorant of his exact date of birth, his father’s identity, and his family ancestry. Nevertheless, through the “grape-vine,” rumor and conversation amongst slaves in slave quarters, Washington learns that his father is likely a white man from a nearby plantation. Washington also learns that his mother’s ancestors endured the Middle Passage, the frightful journey by ship from Africa to America.

Washington lives in a log cabin with his mother, his older brother John, and his sister Amanda. The log cabin is poorly constructed and open to the elements. The cabin’s wooden structure has numerous holes in its sides, an ill-fitting door, and no wooden floor. The naked earth serves as the floor, instead. In all manner of weather, the cabin is uncomfortable. In winter, Washington and his family find it impossible to keep warm. In spring and summer, they find it impossible to keep dry.

Because Washington’s mother labors as the plantation’s cook, Washington’s cabin also doubles as the plantation’s kitchen. Many of Washington’s earliest memories are of the treats his mother procures as cook, including of a time when she woke him up in the middle of the night to eat chicken.

Washington’s small size makes him suited only for a small number of tasks on the plantation. He is often ordered to sweep the yards or to carry water out to the enslaved men in the fields.

His most dreaded task is going to the mill, which is three miles away from his plantation. On trips to the mill, slaves and other attendants load a horse with large bags of corn. Invariably, over the course of the long journey to the mill, however, the bags would shift and fall off. Unable to lift and reload the bags of corn himself, Washington would have to wait on the side of the road for passerby. Washington would sometimes have to wait for hours. During these times, he is always terrified because stories circulate amongst the slaves that deserted soldiers like to hide in the woods and lop off the ears of small, black boys.

Washington first gains self-knowledge as a slave when he hears his mother praying for President Lincoln’s soldiers to prevail in the Civil War. The experience of the war is very different for Black people and whites. Though deprivation is widespread during the war, Washington writes that the whites suffer more because they are used to certain luxuries, while the slaves are used to being resourceful. One of the young masters on Washington’s plantation is killed in the war, a death which Washington reports was met with sorrow even among the slaves.

When the war ends, Washington’s master calls all his slaves to the big house and reads the Emancipation Proclamation aloud. The slaves immediately rejoice and revel in the ecstasy of freedom. This ecstasy soon gives way to apprehension. Most slaves, unfamiliar with life outside of slavery, are not necessarily prepared to enter society. Older slaves, especially, left the plantation only to return to bargain with their former masters for positions that very much resembled the ones they held during times of enslavement.

Chapter 2: Boyhood Days

Newly freed slaves have two immediate and pressing desires, according to Washington. The first desire is to change their names to mark their self-possession. During slavery, the enslaved were generally only referred to by first name. Following emancipation, former slaves take last names and middle initials to mark their new status. The second desire is to remove themselves, if only for a few days, from their home plantations to feel truly free. Many former slaves had never left their plantations prior to emancipation. Nevertheless, as Washington has noted previously, many slaves, especially older ones, would return to their former plantations after a short spell to negotiate labor contracts with their former masters.

Washington moves with his family—his mother, his stepfather, his brother, and his sister—to Malden, West Virginia. There, Washington’s stepfather secures a job as a laborer in a salt-furnace. The family’s new home resembles their old slave quarters. They live in a poorly constructed log cabin amongst a cluster of log cabins.

Nonetheless, Washington embraces his newfound liberty by pursuing his desire to learn how to read. Shortly after arriving in Malden, he asks his mother to get books for him. She procures a Webster’s spelling-book and with it, Washington masters the alphabet. Washington soon exhausts the spelling-book and then seeks out a teacher, but finds that no one in his community can read. Washington’s education languishes for a time, but when a young, literate Black boy from Ohio arrives, his fervent desire to read is reignited. Soon after this scene, another young, literate Black man from Ohio arrives and offers his services to the community as a teacher. Because the Black people do not have a school, the teacher circulates amongst their cabins for a small fee, spending a full day with each family. In this way, Washington begins to further his education. Washington notes that his desire to read is not unique and that many of his race hunger for education.

By the time a nearby school opens in nearby Kanawha Valley, Washington works alongside his stepfather at the salt-furnace and cannot attend. The resulting disappointment spurs Washington to seek out night lessons. When Washington starts attending night lessons, he notices immediately that he is the only student without a hat or cap. His mother cannot afford to buy him one, so she makes him one. The other students ridicule Washington for his hat. He also takes his full name—Booker Washington—because of his experience at school, after learning that all other students had two names.

Chapter 3: The Struggle for an Education

Shortly after securing a job at the coal-mine adjacent to the salt-furnace, Washington overhears talk of a school for Black people in Virginia. The school, Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Virginia, offers students the opportunity to work for their room and board as they learn a trade or industry. Upon hearing of this school, Washington resolves to go to Hampton. Still, he continues to work at the coal-mine for some months before changing jobs to work for Mrs. Viola Ruffner, the wife of General Lewis Ruffner, the man who owns both the coal-mine and the salt-furnace.

Washington is apprehensive to work for Mrs. Ruffner due to her reputation as a strict mistress. Before Washington, Mrs. Ruffner dismissed several former servants who did not perform their duties to her standards. Washington’s fear of Mrs. Ruffner leads him to observe, learn, and adopt her ways fully. Mrs. Ruffner liked everything clean, all labor completed thoroughly and promptly, and complete frankness and honesty in communication. Washington reflects on this experience as a crucial step in his education, instilling within him a love for order and cleanliness, as well as an attention to detail. During this time, Washington begins his first library. He converts an old dry-goods box into a “library” by filling it with every book he can find.

By the fall of 1872, he sets off to Hampton. For his journey, Washington has very little money and only a small satchel with a few items of clothing. To get to Hampton, which is 500 miles away from Malden, Washington must take both stagecoaches and trains. He begins his journey by stagecoach. He immediately realizes, only a few hours away from home, that he does not have enough money to complete his journey to Hampton. When the stagecoach stops for the night at a hotel, Washington feels embarrassment for his lack of money. Before he can communicate this to the hotelkeeper, however, he is turned away due to his skin color. This episode is the first time that Washington learns the meaning of his skin color as a freeman.

By walking and hitching rides, Washington arrives in Richmond, Virginia, which is only 82 miles from Hampton. He does not have any money and does not know anyone. He walks the streets until midnight and decides to sleep on the ground under a raised sidewalk. In the morning, Washington realizes that he is sleeping near a shipyard. He sees a large ship nearby and asks the captain to allow him to unload the ship for money to buy food. The captain agrees and is so pleased with Washington’s work that he allows him to work for him for several days. To save money, Washington continues to sleep under the raised sidewalk. In this way, Washington raises enough money to secure transportation to Hampton.

When Washington arrives at Hampton, he has fifty cents in his pocket. The first sight of the school’s main building arrests all his senses and touches him deeply. He feels a new life begin. When he goes to the head teacher to seek admission to the school, he is deferred though he watches her admit several students after him. Washington attributes this to his shabby appearance, the result of going so long without proper food or bath. After hours of waiting, the head teacher asks Washington to sweep the adjoining recitation-room. Washington sweeps and dusts the room with great care, going over it several times. The head teacher inspects the room and cannot find fault. She admits Washington to the school and offers him a job as a janitor.

Hampton introduces Washington to a new way of life. For the first time, Washington eat meals at regular hours, uses silverware and napkins, and take daily baths. These experiences teach Washington the importance of cleanliness as an inducement to self-respect and virtue. Washington also meets the founder of the school, General Samuel C. Armstrong. Washington describes Armstrong as the perfect man, totally absent selfishness. Armstrong is beloved by other students as well. Washington describes how students volunteered to sleep in tents at Armstrong’s request one winter when the dormitories overflowed. Washington was among the volunteers and describes how each of the students who volunteered felt honored to serve and help Armstrong.

Chapter 4: Helping Others

After Washington’s first year, he does not return home for summer vacation because he does not have enough money. He tries to sell an old coat to get home, but cannot find a buyer who will give him enough money. Instead, Washington finds work at a restaurant at Fortress Monroe and spends his nights studying and reading. He hopes that he will earn enough money to pay back his sixteen-dollar debt to Hampton. The money he earns barely covers his board and Washington is unable to save much money despite his disciplined frugality. One day he finds a ten dollar bill on the floor and reports it to the owner. The owner pockets the money. Washington describes his disappointment in this moment, but says he was not discouraged. Though Washington does not find enough money to pay his debt to the school, the treasurer allows him to reenter for a second year if he agrees to settle the debt when he has the money. During his second year, the selflessness of many individuals at Hampton deeply impresses Washington. He considers this the most important aspect of his education at the school. He begins to faithfully read the Bible, reading a portion of chapter each morning before work. He also begins to develop his facility as a public speaker by joining the debating societies at Hampton. Washington does not miss a single meeting for his entire career at Hampton.

Due to gifts from his teachers and money sent from his mother and brother, Washington can afford to return home after his second year. Upon arriving, he is besieged by requests from the community’s Black population to visit and give talks. He speaks at churches and numerous other gatherings about his experiences at Hampton. Washington expresses annoyance at this. He also expresses disapproval upon finding that both the town’s salt-furnace and its coal-mine are not in operation due to a worker’s strike. Washington notes that most workers suffer and gain nothing because of the strike. Unable to find work in Malden due to the strike, Washington sets off for a nearby town to inquire about a job. On the way home, exhaustion overtakes Washington and he decides to sleep in an abandoned house. His brother John finds him there early the next morning and breaks the news that their mother has died. This news shatters Washington and throws the entire family into disarray.

Without Washington’s mother, his family has no one to do the washing or to cook meals, and each of the family members’ clothing goes unattended. Amanda, Washington’s younger sister, is too young to keep home and Washington’s stepfather cannot afford to hire a housekeeper. Washington describes this period as one of the toughest of his life. Washington continues to seek out work and finally secures a positon with his old employer Mrs. Ruffner. Washington briefly considers not returning to Hampton, but soon vows to not give up without a struggle. Fortunately, he receives a letter from head teacher Miss Mackie requesting his early return to help her prepare the dormitories and the campus for reopening. Washington describes the effect of seeing Miss Mackie, a woman of status, laboring and cleaning as a life-changing. He says that any school that fails to teach the dignity of labor is inadequate. After Washington graduates Hampton, he is once again without money. He finds a summer job as a waiter in Connecticut. The manager assumes that Washington has experience as a waiter, but Washington makes an early mistake that gets him demoted to dish-carrier. Washington, undeterred, studies the art of waiting tables and gains his positon back in several weeks.

At the end of the summer, Washington returns to Malden and begins to teach at the Black school. He describes this period as one of the happiest of his life. His curriculum extends beyond “mere book education” to emphasize proper grooming, personal comportment, and personal industry. In addition to teaching at the Black school, Washington starts a night school, debating societies, and establishes a small reading room in Malden. Washington observes that during this time the Ku Klux Klan is at the height of its activity. During that time, Washington believed that there was little hope for reconciliation of the races. At the moment of his writing, however, he recalls the moment only to measure the distance from which both races have travelled on the road to full reconciliation.

Chapter 5: The Reconstruction Period

During Reconstruction, a period Washington defines as the years 1867 to 1878, Washington is a student at Hampton and a teacher in Malden, West Virginia. Two fads occupy the minds of Black people during this time: the desire to hold political office and the desire to learn Latin and Greek. Washington describes these desires as product of a people less than a generation removed from slavery. Though he admires the fervent desire of many Black people to attain education, he dismisses the idea that educational attainment alone will make one’s troubles go away or free one from physical labor. Washington observes that some members of his race attain minimal education in order to live by their wits rather than their hands. Both the ministry and the schools suffer as a result. Despite this tendency amongst some, Washington believes that both the ministry and the schools show steady growth.

During Reconstruction, the Black population relies heavily on the Federal Government. Washington observes that this is to be expected. He also laments the lack of provisions in place before the decree of emancipation. The absence of readily available education and property for the formerly enslaved results in a “false foundation” for Black advancement socially and politically. Washington recounts a story where he overhears some brick-masons call for a “Governor” to hurry up as they complete a job atop a roof. After inquiry, he later finds out that this man is the Lieutenant-Governor of his state. Washington emphasizes that not all Black politicians are ill-equipped for their jobs, but that the overall lack of experience in politics and lack of education characteristic to the race leads to expected mistakes. Because of this, Washington says he is not opposed to laws that limit suffrage, but says that those laws should apply equally to white and Black people alike. He believes that Black people are better situated than they were thirty-five years ago, and says that the best way to solve political dispute across the color line is to hold both races to the same standard with respect to political and civic participation.

After teaching in Malden for two years, Washington leaves to take classes in Washington, D.C. At the institution he attends, there is no industrial training and he finds that the students are wealthier, better dressed, and occasionally more brilliant. Still, Washington observes that the lack of personal industry displayed by these students makes them less independent and more consumed by outward appearances. He says that these students do not begin at the bottom with a solid foundation and that many, upon graduation, seek out work as Pullman-car porters and hotel waiters, rather than reinvesting their talent to support the uplift of the race. While in Washington, D.C., Washington also observes the lives of many Southern migrants. He says that they can make good lives in Washington, many securing minor government positons and other stable work. Amongst this class of Black people, however, Washington observes a certain superficiality. He comments on how freely they spend money and note their dependence on the Federal Government. He says that rather than desire to make a position in society for themselves, these people want the Government to make a positon for them. Washington imagines the impact that moving these people to the neediest districts of the South would have on them and the race. Lastly, Washington observes that many of the women of these families enter school and learn to have their wants increased without any knowledge or skill to supply for themselves those wants.

Chapter 6: Black Race and Red Race

During the time that Washington spends in Washington, D.C., there is political unrest about moving the capital of West Virginia. Of the three candidates for the new state capital is Charleston, a town five miles away from Malden. The city of Charleston invites Washington to speak on behalf of its candidacy for state capital. Washington travels to West Virginia and makes many speeches in support of Charleston, and Charleston is successful in securing the capital seat of government. This campaign helps Washington further establish his profile as a public speaker and results in numerous calls for Washington to take political office. Washington declines, however, because he believes that other work will best serve his race. He states further that political service invites a selfish kind of success of a very individual nature. He notes that many of the portion of his race entering college do so with an intent to enter law or politics. Washington says that he believes that his role is to prepare a way for their success. To illustrate his point, Washington tells a parable about an old former slave who desires music lessons. The older man asks a younger man to teach him. The younger man responds that the first lesson is three dollars, the second is two dollars, and the third is one dollar, and the last, only twenty-five cents. To this the older man replies that he only wants the last lesson.

Soon after Washington finishes his campaign on behalf of Charleston, General Armstrong invites him back to Hampton to deliver the commencement address. Washington returns to Hampton and is astonished to see that in the time he has been away, there has been a railroad set straight to the town. Washington delivers the address and returns home. Soon after returning home, he receives another letter of invitation from General Armstrong asking him to join the faculty at Hampton. Washington starts work at Hampton as a teacher of Native American students. Washington says that before this period, few people had confidence that Native Americans could receive education. Washington lives with the Native American students in the dormitories and becomes their teacher, introducing them to correct discipline, clothing, and personal comportment. Washington begins the job apprehensively, but soon finds that the Native American students differ in no fundamental way from Black students he has otherwise taught. He notes the Native American students’ capacious love and respect, and says they always aimed to increase his happiness and comfort. Washington relates that the aspect of education that the Native American students’ felt most difficult was cutting their long hair. Washington says that the white American only respects those who think, eat, look, act, and profess the same religion as him.

The reception of the Native American students by most Hampton students awes Washington and he comments that he cannot imagine a white institution receiving the Native American students with the same generosity. Washington says that the true test of a gentleman is when he is in the company of someone of a less fortunate race. To illustrate this, Washington tells an anecdote about George Washington encountering a Black man on the road who lifts his hat. Washington lifts his hat in return and his white companions are stunned. George Washington then tells his friend that no Black man is going to show himself more polite than him. Washington continues to reflect on the absurdity of racial prejudice by telling two stories. In the first, he recounts taking an ill Native American student to Washington, D.C. and having to stop for the night. The hotel refuses to give him a room, but welcomes the Native American student. Washington says their skin color is the same tone but that the hotelkeeper has no problem making distinctions. The second episode that Washington describes occurs in an unnamed town when great agitation results from the mistaken belief that a Black man has secured a room at a hotel. When the man clarifies the matter and says that he is Moroccan, the town’s agitated citizens, who were on the verge of lynching, are immediately calmed.

Towards the end of his first year at Hampton, Washington also begins a nightschool. There, students who cannot afford Hampton can work during the day and attend at night. The nightschool starts with twelve students whose dedication and hard work earn them the title of “The Plucky Class.”

Chapter 7: Early Days at Tuskegee

During his first year at Hampton, Washington also pursues further study. Under the direction of the current Principal of Hampton, Rev. Dr. H.B. Frisell, Washington deepens his education. Toward the close of his first year, Washington receives an invitation from General Armstrong to head a new normal school in Alabama. Though the people of Tuskegee were looking for a white man to head the new school for Black students, they happily accept Washington. Washington goes home to West Virginia for a few days before going down to Tuskegee. When he arrives at Tuskegee, he learns that there is no school building, but he is delighted to find that there are many eager students.

He describes Tuskegee as ideal for a school because it is near railroad lines and amid a great Black population. In addition, during slavery times, the town was the center for white education, so the white townspeople themselves possess culture and education. Washington further comments on the cordiality of the relations between white and Black people. He cites the presence of hardware store co-owned by a Black man and a white one as an example. The people of Tuskegee, after hearing about the educational work at Hampton, applied to the Alabama state legislature for money to start a normal school in Tuskegee. The legislature gave them two thousand dollars that could be used to pay instructors. There was no money for land or buildings. Washington describes the task before him, to start a school, as being akin to making bricks without straw.

They first begin lessons in a shanty located near the local church. Both the church and the shanty are in poor condition. During bad weather, a student had to hold an umbrella over Washington as he taught and students completed recitations. Washington says that his time in Tuskegee allows him to observe the everyday life of Black people in the Black Belt of the South. He says that for the most part, Black families sleep in one room. Most cabins lack a place to wash one’s hands or face and usually this provision is located out in the yard. Generally, they eat fat pork and corn bread and occasionally black-eyed peas. Washington also observes their spending habits and the items around their homes. He says that many cabins have sewing machines that were purchased on installments and that often go unused

Washington also notes that few homes have a full set of silverware for each of its members. Despite this, he observes many expensive items in their homes. The families largely still work in cotton-fields and every member who is old enough to labor participates. The families take the weekends off. On Saturdays, the full family goes to town to visit and shop, sometimes dancing, sometimes smoking or dipping snuff. Washington learns that most families’ crops are mortgaged and that most Black farmers are in debt. Because Alabama did not erect any Black schoolhouses, most Black schools are held in churches. Where the communities cannot afford this, teachers and students hold school in log cabins. Washington says that only an exceptional few teachers are prepared and morally qualified to do their work.

Chapter 8: Teaching School in a Stable and a Hen-House

On the cusp of Tuskegee’s opening, Washington feels great trepidation about the challenge to lift up the Black people of Alabama. His tour of their living conditions convinced him of the need to provide them with more than an imitation of New England education. He says mere book learning is a waste of time for them. On the opening day of Tuskegee, the town’s white and Black residents show great interest. Washington credits two men from the town with his ability to get the school off the ground: Mr. Lewis Adams, an ex-slave, and Mr. George W. Campbell, an ex-slaveholder. Mr. Adams never attended school, but learned several trades during slavery. Washington marvels at his power of mind, which he believes Adams derived from the training he received for his hands. Mr. Campbell impresses Washington with his readiness to lend both his aid and his power. Nevertheless, many of the town’s whites believe the project ill-conceived, saying it will corrupt the Black people and they will leave their farms and soon be unfit to secure work as domestic servants.

On opening day, thirty students report to the school. Many of Washington’s students were public school teachers. Washington notes that many of his students had some previous learning and that especially, many of them were proud to have studied large books. Some had also studied Latin and Greek. This prompts Washington to recall one of the saddest sights he saw on his tour of Black communities in Alabama: a young Black boy reading a book of French grammar in a yard of weeds. Nonetheless, Washington finds his students eager to learn. After six weeks, a second co-teacher, Miss Olivia A. Davidson, arrives from Ohio. Washington and Miss Davidson together begin to plan the school’s future. They want to design a curriculum that will best suit the students who come from agricultural backgrounds and have little education by way of social niceties and customs. In addition, they want to provide industrial training. They are briefly discouraged when during their travels, they repeatedly encounter potential students who want an education only so that they no longer have to work with their hands, but they continue with their plan.

About three months after opening day, an old plantation goes on the market near Tuskegee. The asking price is very little, so Washington strikes a deal with the owner. The owner allows Washington to pay half of the full price if Washington promises to pay the second half within a year. To obtain this money, Washington writes to his friend, the Treasurer of Hampton, General Marshall to inquire if he can borrow money from the institution. Marshall replies that he is not authorized to lend the institution’s money, but that he is willing to lend his own. Marshall’s generosity surprises and delights Washington, who is inspired to work to pay him back. The school moves to the plantation. The plantation consists of a cabin, an old kitchen, a stable, and an old hen-house. The school makes use each of these buildings. Students do all the work to prepare these buildings for instruction. After the students prepare the buildings, Washington next tells the students that they will plant crops to raise money for the school. The students do not take to this idea at first, but Washington joins them in the fields and they all soon join in. While Washington lays the foundations for Tuskegee’s financial solvency in this way, Miss Davidson holds festivals and suppers for the town’s residents.

Chapter 9: Anxious Days and Sleepless Nights

Washington describes Christmas in Alabama, which provides him with a deep glimpse into the lives of former slaves. During slavery, Christmas was the one time of year that slaves did not have to work. Because of this, during his first Christmas in Tuskegee, Washington finds it impossible to convince anyone to work after Christmas Eve. The holiday lasts for a week. He describes the week as debaucherous, full of drinking and shouting, with little reference to God or the “sacredness of the season.” Washington makes it a point to teach the students at Tuskegee the importance of the holiday and its proper observance. Washington contrasts this first Christmas in Tuskegee with later memories of Tuskegee students and the good works they do. He recounts a story when Tuskegee students spent the holiday rebuilding a cabin for an elderly member of the community. Washington also reflects on the relationship between the school and the town’s white community. Washington describes the effort he put forth to make Tuskegee a part of the community, rather than a foreign institution.

Next, Washington describes the growth of the school. By holding festivals and concerts, the Tuskegee Institute secures enough money to pay back General Marshall’s loan and to settle the debt for the farm. By growing crops and cultivating animals, Tuskegee also begins to establish a method of generating revenue. This helps fund the school and gives poor students an opportunity to fund their own educations. The success of these ventures allows Tuskegee to plan for a new building. When the plans get drawn up, a local Southern white man who runs a sawmill offers to give the school the necessary lumber for the building. Washington is reluctant to accept this offer because the school did not have any money at that time. The sawmill owner insists and Washington eventually accepts after raising a portion of the sum.

To raise more money for the school, Miss Davidson continues to hold festivals and concerts for the local community. Washington marvels at the generosity of both the white and Black citizens of Tuskegee. Miss Davidson also travels North to raise money, but she encounters trouble because the school is not yet well-known. Nonetheless, many important donations come from Northern people. Washington recounts the generosity of two Boston women, who later become annual donors, and who make it possible to pay the outstanding debt on the school’s first building. Following this donation, the women continue to make $6000 donations each year. The first building is called Porter Hall, named after a generous donor from Brooklyn.

As soon as the first plans for the building are drawn, Washington set students to the digging of the building’s foundation. Though some of the students still resist manual labor, many are happy to contribute to the school’s history and take pride in helping erect the school’s first building. On the day of the laying of the cornerstone, Tuskegee hosts a ceremony that includes many guests. The guests include teachers, students, people from the town, and all the county officials, as well as many prominent white men from nearby towns. The Superintendent of Education for the county delivers an address. Washington marries the next summer, the summer of 1882.

Chapter 10: A Harder Task Than Making Bricks Without Straw

Washington relates his determination to have students do all of Tuskegee’s domestic, agricultural, and industrial work. He says he wants to instill a sense of dignity through labor and to improve students by teaching them the best and most innovative techniques of the time. Many oppose Washington’s idea to have students erect the buildings on Tuskegee’s campus. They point out that the students lack training and experience. Washington is undeterred. Though he acknowledges that most students at Tuskegee come from poor backgrounds and would very much desire to be placed in new buildings, Washington says it’s a more natural progression of development for them to build their own structures of learning. Washington, writing nineteen years into Tuskegee’s existence, reflects on the success and continued adherence to this model.

Nevertheless, the road to this success was a long one and Washington spends considerable time recounting Tuskegee’s first experiments with brickmaking. First, Washington and his students cannot not locate a suitable location to open a pit that produced brick clay. After finding a suitable location, they struggle to mold and burn bricks that hold. Because the burning process takes a week, each failure costs a considerable amount of labor and time. The kiln fails three times before they achieve success. The school develops its brickmaking program to train students in this art and produces bricks for the market.

This experience further convinces Washington that if Black people make themselves useful they will be accepted by whites. Many whites, even those unsympathetic to Tuskegee and Black people in general, come to the school to purchase bricks because of their quality, affordability, and convenience. This leads Washington to believe that the intermingling of business can be a foundation for race relations in the South. Washington further expounds on this idea by saying that there is something in the human spirit that makes it recognize and award merit.

The industrial education at Tuskegee broadens to include the building of wagons, carts, and buggies. Students build these for the Tuskegee campus and for the local community. They also offer repair services to those who need it. Washington reflects that the person who makes himself useful will always find a place for himself in a community. He says that a community might not need someone who can read Greek at this time, but if one supplies what it does need, then one need not worry about being cast out.

Despite the success of his industrial training experiments, some parents protest the requirement that students engage in labor while at school. Nevertheless, Washington remains steadfast in his belief that all students at Tuskegee must learn to labor and to find dignity, pleasure, and self-reliance in it. In the summer of 1882, Washington takes a trip North with Miss Davidson to raise more funds for the school. They stop in Northampton, Massachusetts, where Washington is surprised to be admitted to a hotel. They are successful in raising money and hold their first chapel service in Porter Hall on Thanksgiving Day of that year. This is a landmark moment for Washington.

The school soon grows so large that it is in need of a dining room and a larger boarding department. During this time, despite Washington’s success in raising money for multiple ventures, Tuskegee is still in need of money. Washington describes the first few years as rough. Meals are not held regularly and there is not enough furniture. The furniture that does exist is not well-made, as students had yet to master the art of furniture-making. Nevertheless, this rough start eventually gives way to order and the journey that the students take together to build and better their school guards against any displays of excess pride or snobbery.

Chapter 11: Making Their Beds Before They Could Lie on Them

Visitors from Hampton come to visit Tuskegee and praise the school’s progress. General Marshall, who lent the school money to secure the old plantation, Miss Mackie, the head teacher who gave Washington the sweeping examination, and General Armstrong, the idolized principal of Hampton, all visit and express their pleasure at the fast progress of Tuskegee. Washington recounts General Armstrong’s visit as especially affecting. Washington is surprised to find that General Armstrong holds no bitterness toward the Southern white man despite having fought against him in the war. This generosity of spirit inspires Washington to strive to manifest sympathy for all men and helps him realize that hatred is a tool of small, weak men. General Armstrong teaches Washington that he should allow no person to degrade his soul by making him hate them.

This realization leads Washington to reflect on the issue of the ballot in the South. He says that the action taken to limit Black people’s access to the ballot does more injury to the white man than it does to the Black man. Washington believes the prohibition of Black people from voting is temporary, while the damage that whites invite to their morals is permanent. He also notes that where a white man is willing to commit injustice against a Black man, he is also likely to commit injustice against a white man if so compelled.

Students continue to come to Tuskegee in greater numbers and the school must figure out how to feed and house them. The school rents many log cabins nearby, but many of the cabins are in poor condition. The discomfort that students face worries Washington. On many occasions, in the middle of the night, he stops by the students’ cabins to comfort them. Despite their discomfort, Washington describes the students as happy and grateful for the opportunity to gain an education. Washington elaborates further on the kindness and generosity of Tuskegee students and says that it proves wrong the idea that Black people could not respond favorably to a Black person in authority. He also reflects on the lack of racial prejudice he experiences. The white population of Tuskegee has never said an unkind word to him or treated him poorly. Once, on a train back from Augusta, Georgia, Washington recognizes two white women from Boston whom he knew well. They invited him to dine with them. Washington is at first apprehensive because of the tacit segregation common in the South. The train is otherwise full of Southern white men. Nevertheless, Washington dines in their car with them and then takes leave to go to the smoking-room, where most of the men are seated. Once there, Washington is surprised to receive warm greeting and thanks from many men who are impressed with the work he is doing.

Washington tells Tuskegee students that the institution is theirs and encourages them to come to him with any problems or concerns. He says that the best way to dissolve disputes is through open and honest communication. Next, he describes the first attempts at mattress making at Tuskegee. Because many of the students are poor and the school does not have extra money, the students must make their own mattresses. Most students take two large bags, sew them together, and fill them with pine straw. Despite this and their often poorly made furniture, Washington enforces a standard of absolute cleanliness. This extends to the body, as well. He requires students to bathe and to keep clothing tidy and clean at all times.

Chapter 12: Raising Money

The inability to house all students comfortably continues to wear on Washington, especially as the school admits more and more women. Because of this, the school decides to build another, bigger building to expand the boarding department. Miss Davidson begins to raise money around Tuskegee from both white and Black citizens. The money that she raises from local citizens is not enough to erect a new building. After some time, General Armstrong writes and asks Washington to join him on a tour of the North. He and the General tour with a group of singers to important cities and hold meetings and give speeches. Though General Armstrong and the Hampton Institute cover all the expenses for this tour, General Armstrong tells him that this effort is on behalf of Tuskegee. In this way, General Armstrong introduces Washington to many important people in the North and further solidifies his image in Washington’s mind as the most selfless man in existence. They tour New York, Boston, Washington, Philadelphia, and other large cities.

After this first experience in the North, Washington continues to go by himself for some time. He elaborates his rules for asking for money from philanthropists. He says that the first duty of such work is to make one’s institution and values known. The second is to not worry about the outcomes, no matter what bills or debts pile up. Washington also notes the qualities of accomplished men, with whom he has begun to come into contact: self-possession, patience, and politeness. Washington says that to be successful, a man must entirely forget himself for the sake of a great cause. His happiness will result in proportion to the degree that he accomplishes this.

Washington describes the anxiety of having to constantly be away from Tuskegee to raise money for the school. Despite the persistent money troubles in the first few years of the institution, Washington is determined to succeed because he believes that Tuskegee’s failure would have ramifications for the entire race. This drives Washington on through the difficult years of raising funds for the school. Finally, Tuskegee begins to receive many large donations, the largest of which is $50,000. Washington credits this to the hard work and persistence of establishing the school and its reputation. He says that luck is only won through hard work.

Washington recounts his experience meeting Andrew Carnegie, who eventually donates $20,000. He describes Carnegie as distant. During their first meeting, Carnegie shows little interest in either Washington or the school, but when Washington writes to him to appeal on Tuskegee’s behalf, he is surprised and delighted by Carnegie’s willing generosity. In addition to these large donations, Tuskegee also receives small donations from all around the country. At the beginning of the third year of the school, the State Legislature of Alabama votes to increase the annual appropriation to Tuskegee. This and annual donations from the Slater and Peabody Funds ensure that Tuskegee can continue to operate in financial solvency.

Chapter 13: Two Thousand Miles for a Five-Minute Speech

Tuskegee establishes a night-school in 1884 to accommodate students who cannot afford to attend the institution. Tuskegee models its night-school after the night-school at Hampton Institute, requiring students to work for ten hours during the day at a trade or industry and to study for two hours in the evening. Only students who cannot afford the board of day-school can attend. The Treasury keeps all but a little of the students’ wages, so that when students eventually transfer to the day-school they have means to pay their tuition. This process usually takes two years. The difficulty of the night-school is the most severe test of a student’s dedication and commitment due to the long hours and level of discipline the program requires. Washington observes that many of Tuskegee’s most successful students began their study at the night-school.

Following his Northern tour with General Armstrong, Washington’s career as a public speaker continues to blossom. He receives more invitations and begins to better develop his ability. He credits his popularity and success with his willingness to level honest criticism without condemning an entire race for the situation of his people. Washington credits this sensitivity with lessons he learned in his early years. As a young man, Washington held onto bitterness toward anyone who spoke ill of Black people or made barriers to their advancement. Maturity teaches him to recognize, however, that those who hold such beliefs do more damage to themselves than anyone else. Most of Washington’s early speeches serve to raise money for the school. An early speech in Atlanta at the international meeting of Christian Workers earns him an invitation to speak at the esteemed Atlanta Cotton States and International Exposition, where he delivers one of the most famous speeches of his career.

Before delivering this speech, Washington travels with a committee of people from the Exposition to the nation’s capital to address Congress. In his speech to Congress, Washington argues that Black people should not be deprived of the ballot, but says that the ballot means little if Black people do not also develop and attain property, industry, skill, economy, intelligence, and character. After this speech and the trip to Washington, D.C., the directors of the Exposition decide to devote an entire building to exhibitions about the accomplishments of the Black race. The largest part of this is devoted to exhibits on the Hampton Institute and the Tuskegee Institute. As the day of Washington’s speech approaches, he feels great trepidation due to the widespread coverage his upcoming speech receives in newspapers and the anticipation it inspires. Before setting off to Atlanta, Washington delivers his speech to the teachers of Tuskegee. Washington ends the chapter by describing how his close friend, a white man, Mr. William H. Baldwin, Jr., is so nervous for Washington that the refuses to enter the auditorium and instead paces back and forth for the duration of Washington’s speech.

Chapter 14: The Atlanta Exposition Address

Washington includes the full text of his address to the Atlanta Cotton Exposition. As soon as he finishes his speech, Governor Bullock and other prominent white men rush to shake his hands and congratulate him. His speech is so well-received that Washington has trouble exiting the building. He returns to Tuskegee the next morning. There he is delighted to find that nearly all major newspapers in the United States cover his speech favorably. He includes the text of many of these newspapers within the chapter. What touches Washington most, however, is a letter from President Grover Cleveland, who praises him for the hope and determination of his words. Washington eventually meets President Cleveland when the president visits the Atlanta Exposition. Washington describes him as a simple man full of grace and patience. They begin a friendship and Washington relates that President Cleveland does everything in his power to help advance Tuskegee.

The Black papers have more mixed reviews of Washington’s speech at the Atlanta Exposition. At first, they receive his speech well, but then criticisms begin. Many charge Washington with speaking too little about the violence against Black people and too little about political rights. Washington calls these responses reactionary and states that nevertheless many of these critics were eventually won over. Washington relates this criticism to earlier moments in his career when he received criticism for speaking about the inadequacy of many Black ministers. Despite the outcry of many Black newspapers, many prominent Black bishops and church leaders agree with Washington’s assessment and the criticism is eventually quelled.

After the success of his speech, Washington receives an invitation to serve as a judge of an award in the Department of Education. This touches Washington deeply and he sits on a board of jurors that numbers sixty. The jurors include college presidents, leading scientists, famous writers, and specialists in many fields. Washington reflects on the political future of Black people and predicts that Black people will reach full citizenship when they have reached the level of development that entitles them to its exercise. He believes that the issue cannot be forced from the outside and that Southern whites will decide on their own to welcome the Black population into society without restriction. He believes that there is a change in that direction already underway. To illustrate this, Washington cites both his invitation to deliver a speech at the Atlanta Exposition and his invitation to serve on the juror committee. Both would have been unthinkable just a year earlier.

Washington believes that slow, steady progress will best produce an equitable South. He decries laws that allow an ignorant and poor white man to vote and not a Black man. He says that the law should apply equally across the color line. Nevertheless, he believes that Black people must develop themselves to exercise the ballot responsibly. Though Washington believes in universal suffrage, he believes that the peculiar circumstances of the South require special provisions and the protection of the ballot, either by property test or by education test.

Chapter 15: The Secret Success of Public Speaking

Washington opens this chapter with a summation of how his speech at the Atlanta Exposition was received by the people present in the audience. He includes the full review of a journalist, Mr. James Creelman, who praises Washington’s speech and his person. Following the speech at the Atlanta Exposition, Washington accepts invitations to speak as much as his commitments at Tuskegee allow. The frequency of the requests to speak surprise Washington. Each time he speaks publicly he suffers from great nervousness, but says that he knows no better pleasure than mastering an audience and becoming one with them. He describes the sensation and immense satisfaction of going at unsympathetic audience members and working them over to his side. Washington says that great speeches must come from the soul and shares that he endeavors to make his speeches so interesting that no one leaves the room while he is speaking. Washington most prefers to speak to businessmen after they have had a nice dinner. After this group, Washington most prefers Southern audiences. Washington also makes a point to speak to Black communities across the country. This allows him to see the living conditions of Black people in the United States firsthand.

In 1897, Washington receives a letter inviting him to deliver an address at the dedication of Robert Gould Shaw, a white colonel killed in the assault on Fort Wagner. This experience deeply touches Washington and causes him to reflect on the Spanish-American War. Shortly after, he delivers a speech at the University of Chicago where he praises the efforts of Black soldiers in the Spanish-American War and celebrates the history of Black patriots. President William McKinley attends the speech that overflows the auditorium in which it is held. A portion of this speech generates criticism from many Southern newspapers who demand that Washington clarify what he means by “social recognition.” Washington responds to these criticisms publicly and reiterates the positions laid out in his Atlanta Exposition speech.

Washington can undertake such a heavy schedule of public speaking because Tuskegee is supervised by teachers and the Lady Principal when he is away. In a year, Washington averages six months away from Tuskegee. Washington is encouraged that Tuskegee can operate when he is away because he believes it testifies to the strength and organization of the institution. Nevertheless, when Washington is away he uses a system of correspondence to stay consistently abreast of the activities at the school. An average day in Washington’s life is full of responsibilities. Because of this, he makes it a rule to clear his desk by the end of each day, to leave no task unfinished. The one exception that Washington makes to this rule is when he an unusually difficult decision to make. Then, he waits until he has a chance to talk with both his wife and his friends. Washington also relates small personal details about his life. He does not enjoy games, but finds that keeping a garden relaxes and enriches him. He also enjoys caring for animals. Though Washington rarely takes breaks, after nineteen years of constant work, his friends press him and his wife to take a vacation to Europe. He at first declines, but eventually accepts later.

Chapter 16: Europe

In 1893, Washington remarries after his first wife dies. He marries Miss Margaret James Murray, the Lady Principal of Tuskegee. The new Mrs. Washington proves to be an immense help in more efficiently running the school. Washington describes their ability to cooperate in the interest of the school as seamless. Washington says that the thing that bothers him most about his life’s work is how often it has kept him away from his family and his children. In 1899, Washington attends a distinguished meeting in Boston where several people notice he looks more tired than usual. Two women press him on it and implore him to take a vacation. A close friend, Mr. Francis J. Garrison, raises enough money to pay for a full summer trip to Europe and, along with the ladies, implores that Washington and his wife take a vacation. Washington begrudgingly accepts and leaves the United States for the first time in his life.

Washington is apprehensive about how people will respond to his taking a vacation. He does not want people to think him pretentious for spending a summer in Europe. This fear and his guilt about not working for so long a time plague Washington before he sets out on his trip. Washington and Margaret set off to Europe at the start of the summer with many letters of introduction to people across Europe, especially in England and France. On board the ship, the Washingtons meet several prominent people including a senator and an influential journalist. They are also delighted to find that the captain greets them personally. Washington says that as soon as the ship moved away from the wharf, he felt a huge weight lift from his soldiers. For the first few days, Washington sleeps a great deal.

The ship lands in Antwerp, Belgium. The Washingtons spend a few days there and then a group invites them on an excursion to Holland. The manner of agriculture and the excellence of cultivation in Holland impress Washington greatly. After this brief trip to Holland, the Washingtons return to Belgium and from there, set off for Paris. In Paris, they meet up with Elizabeth Cady Stanton, an anti-slavery and women’s rights activist. They are invited to many high-profile events in Paris and meet many distinguished people. They also encounter the famous Black American painter Henry O. Tanner. Tanner impresses Washington a great deal and makes him believe more strongly in power of merit to overcome the prejudice of the color line. The French people impress Washington with their love of pleasure and excitement. Washington says that he does not believe the Frenchman to be ahead of the American Negro and believes that the future will show that the American Negro far surpasses the average Frenchman.

From Paris, the Washingtons travel to England. In England, the Washingtons likewise visit with many distinguished guests. The country houses of England make the deepest impression upon Washington, who describes them and the life they allow as perfect. He also marvels at the efficiency of English homes in general and the lack of pretention amongst the servants. He credits his trip to England with deepening his regard for nobility and praises the character of the English in its entirety. On the ship back home, Washington finds a copy of Frederick Douglass’ biography in the library and reads it.

Chapter 17: Last Words

Washington reflects on his life and says that it has been full of surprises, but that he believes that anyone’s life can be full of surprises if he or she is willing to give his or her absolute best, living purely and selflessly, each day. Nonetheless, fortunate and unfortunate surprises befall Washington. General Armstrong, who a year earlier was stricken with paralysis, desires to see Tuskegee one last time before he dies. The school holds a torchlight reception in his honor. The General is overcome by the demonstration. General Armstrong dies shortly after. Washington’s greatest surprise is the moment he opens a letter from Harvard University that says it wishes to confer upon him an honorary degree. Tears come to his eyes as he holds the letter. He thinks of his whole life in that moment: his former slave life, his work at the coal-mine, his struggles to get to Hampton, his first difficult days at Tuskegee, and the general oppression set out for people of his race. He is deeply moved.

Washington goes to Harvard and sits through the ceremony and is afterwards invited to dine with the University’s president. Washington recalls the entire experience as one of his fondest memories. Soon after, Washington convinces President McKinley to visit Tuskegee after he hears that the President will be in Atlanta, Georgia for an official visit. The President comes to Tuskegee with his wife and all but one of his cabinet members. A huge crowd of students, teachers, and locals receive the party. Citizens decorate the entire town in preparation for the President’s visit. The students of Tuskegee host a parade in the President’s honor. The President delivers an address. Reflecting on this moment makes Washington marvel at how far Tuskegee has come. He describes the mission of Tuskegee as preparing students with three main goals in mind: to give the student the ability to enter a community and perform the work that needs to be done, to enable the student to become self-sufficient and be able to support himself, and to develop a love of labor.